My previous post, in its rambling way, attempted to raise the following issue:

Economics – more than all other subjects, I think – faces a difficult task of finding the balance between novelty and topicality on the one hand, and a curriculum which coherently builds knowledge on the other. The danger on one side is a jumbled mess of ideas with roots in the past, in contexts and ideas which all require explanation and shouldn’t be assumed, and on the other an unchanging, technocratic subject, more akin to maths, with glaring holes where topicality should be; and this in a subject which could or should be the most applied of them all.

I am not claiming this balance is impossible to strike, merely that it is harder and more important than I used to think – and I think it’s getting harder.

In this post I want to cover a bit more about why this problem emerges, what has been done from the top down, and what can be done from the bottom up. I profess no particular expertise on this, and make no claim for the efficacy of some of the things which I try to do. In many ways, there is nothing new in the conclusions – such as they are – I come to; this is all familiar stuff in the world of teaching blogs of recent years. This is reflected in a final section, where I reflect on Martin Robinson’s post this week, which was partially a response to my Part 1.

Again, it will, by its nature, allude to future posts yet to be written. This post is more than long enough (sorry about that). I have a fear this entire blog might become one extended concatenation of ideas…

*****

Keeping up with a changing world

Firstly, I absolutely want to avoid the no-context, no-application end of this dilemma. Economics is indeed a powerful subject for explaining the world around us; teachers and students thrive on this, students expect it, and it is, ultimately what the subject attempts to do.

Economics, though, as we are oft-reminded, is not a science. Despite its best efforts it does not advance in the same way science does. As new ideas and insights come to light, they don’t always (often?) replace previous ideas, they mingle with them instead. As people like Dani Rodrik argue, there is perhaps no such thing a settled “economics”, but rather different sets of ideas for different times and different circumstances. So it’s only right that we adapt to our times and circumstances.

Part of this is, of course, embedded in our specifications: “Students should have knowledge of the UK economy in the last 10 years” says Edexcel; “It is expected that students will acquire a good knowledge of trends and developments in the economy which have taken place over the past fifteen years and also have an awareness of earlier events where this helps to give recent developments a longer term perspective.” says AQA.

(You may be able to guess from my posts which one of these I prefer)

This is what I mean by this problem being unique to Economics; I don’t know of any other A Level which is that explicit in its requirement to be topical. And nor am I against it (I’d actually love to see more of this in Business, which lost a lot of topicality in the 2015 reforms, in my opinion). My contention is that to really meet that criterion, you need a lot more knowledge, and of a particular kind, like Martin’s T-shaped curriculum. The UK economy of the last 10 years only exists in the context of what came before, and what came before that. It is defined by what it no longer is, what it used to be; by contrast, by evolution. And it will be so in the future.

For example, it’s interesting to remember that the general use of inflation targeting and independent central banks is only a generation old, and there are plenty of advocates of change around – like David Beckworth and Scott Sumner – arguing for new targets, and these ideas are gaining some traction. It’s not implausible that we could have new regimes for central banking to teach in the next decade, but I think we will only be able to do that well with reference to the inflation targeting of today. With the social and economic fissures exposed by Covid-19, there could be a new social contract in the future; UBI type ideas don’t seem to be going away. Economics and the economies it studies are both evolving; we have to try and keep up.

*****

Superficiality

Ofqual and the exam boards tried to keep up in the 2015 reforms. Essentially, they tried to plug some gaps in the A Level specifications – topics which maybe should have been there but weren’t. But I’m not so sure they succeeded: I wonder if they were actually seduced by topicality, in a subtle way.

The additions of Behavioural Economics and Financial Markets still don’t quite, in my opinion, sit that comfortably in the overall syllabus. Again, I think a full discussion on the Economics curriculum will have to be another post (or several). I’ll merely say here that they still feel somewhat tacked on*, with something of the air of planning for the previous war, and that for example we have seen during Covid-19 that there is not really any such settled thing as Behavioural Science or Behavioural Economics; its insights remain somewhat sketchy and have in no way replaced the mainstream, remaining more of a critique rather than an alternative model – the topic mostly remains optional at degree level.** At the same time, AQA added specific reference to changes in monetary policy, and not just the well-known Quantitative Easing: though moderated by the get-out clause “such as”, they mention Funding for Lending and Forward Guidance, the latter of which has a 15-line Wikipedia entry (an imperfect measurement of significance, but I think it tells us something about how important that term became).

This, then, exemplifies twin dangers. Firstly, it is really difficult to latch onto changing ideas as they evolve. I think I’m right in saying it took about a century for Relativity to make it onto the Physics A Level (I remember doing it as an extra, fun topic when doing S Level)! All sorts of subjects evolve and add new ideas to their corpus of core knowledge, but I’m not sure any others do so in quite as breathless and excitable way as Economics. This can lead to controversy, debates over what constitutes the core foundations of the subject, and insertions of current ideas before they are settled, both at an exam board and a teacher level. Will we be adding “recessions due to pandemics” to the next specification?

Secondly, this gives rise to a level of superficiality which I find at least slightly disheartening, and, as I confessed in Part 1, I think I am certainly guilty of, though more so in the past. If you’re covering a topic because of a “such as” in an exam board spec, or because it’s a current interesting area of focus in the real world, how much depth do you really go into? Do you have the time to give it the full background it needs to be properly understood? Is it enough for students to have in their arsenal a few lines of brief description of an idea? Will they be examined directly on it? How does it fit with the core topics? Is it just an extra? Is it just for the most engaged and interested students as additional “evaluation” material? Are we simply aiming for students to have just about heard of a lot of things, but with no real unifying structure to them? And most importantly for teaching, is it within the abilities of those whose core knowledge is weaker; is it accessible to all?

The financial markets content is a case in point here. Yes, Economics had failed to incorporate financial markets fully into macro; this was a central tenet of post-financial crisis critiques of the subject. But at least part of the reason it wasn’t in A Levels must surely have been that it is hard and complex, and difficult to understand at this level. I think we’ve done a reasonable job at trying to incorporate it into the A Level, but I think most would admit that it just scratches the surface, the questions the exams ask about it are limited, and the whole thing, I think, has an air of tacked on superficiality to it. I will hold my hands up and admit that you don’t have to stray too far from the A Level before my own knowledge and understanding in this area is exhausted (not least because, as per the critiques of the subject, it wasn’t a big part of my education). And, let’s be honest, money creation and banking remains controversial and debated well beyond the school classroom. It’s only a few years since a famous 2014 Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin on Money Creation, and debates about Helicopter money and Modern Monetary Theory are ongoing. When the content is not agreed upon in the “real world”, it is hard for us to teach it beyond mere glib superficialities.

*****

On an Overgrown Path

So we do want to retain a lot of topicality in the subject; we have to. But I think this needs really careful consideration. Lobbing stuff in at the specific behest of the exam board, or keeping students up to date with “what’s going on” is important, but a) I think it’s vital to place this context, and b) exam boards and teachers need to consider what it is we really want students to know, and when (yes, this was a trendy curriculum blog all along).

Think about the economics of Covid-19. Although relatively easy to understand, by and large they simply do not fit into our standard textbook models of Aggregate Supply and Demand. Rather than enacting simple fiscal stimulus, intending to bolster spending in the economy, governments around the world are deliberately constraining spending in the economy, but creating emergency support for people’s incomes. The Supply side, to the extent it is reduced, will mostly be so because of the loss of institutional memory and organisational capacity, a withering away on the vine of previously viable firms; a complete change of the economic structure thanks to a massive exogenous shock. We can’t really put that in our standard model and diagram at A Level.

We can easily teach this in its surface features, but what makes the economics of today interesting, is that it is different from what came before. So my instinct here is that a student is only really going to understand this in reference to what it is not. It is not the previous recession; the responses are not the same; you’re better off seeing it through that lens than squeezing it into a pre-determined model. And so the pressure to be topical is also a pressure to have more background; the subject just keeps expanding.

So what does that mean? I think it all implies two or three things which I try to do in my teaching and planning. These are by no means “the answers”, but they do form a big part of what has been a previously unspoken teaching philosophy, but also, by implication, my views on what the exam boards should be aiming for. They are also by no means original or new – I’m sure many, many readers also keep these ideas in mind.

Firstly, over time I have increasingly adopted a walk before you can run approach. I think I will return to this in another post, but it took me a while to really internalise the “learners as novices” idea which thankfully is now reasonably well-understood. This is an especially jarring problem at A level, as we teach what appear to be young adults, often literate and worldly, but crucially naïve in formal economics. Most other subjects can pick up a Y12 student and carry on where they left off from Y11; we start from scratch. We don’t do A Level maths before we have our basic arithmetic.

As the teaching tide has turned, ebbing away from “engagement” and towards deliberate instruction and careful curriculum planning, so has my practice, and I advocate a pretty big distinction between the first and second year courses.

There is nothing really new or controversial here, as this is how the A Level course is generally structured anyway. But even so, my first year is more abstract than it used to be. There are no research tasks. There are lots of tests. We study the core models. There is directed and selected reading. I will blend in some contemporary content if and only if students have covered what I think are the prerequisite areas of knowledge. I have attempted to give careful thought to the sequencing of ideas.

But this is not costless; it does mean I forgo those tempting topicalities, often letting them pass by whilst I continue down my predefined path. I try to avoid tempting detours, and that is a loss.

Around this time of year, the summer term after the “first year course” but before end of year exams and the like, I branch out. In the past I have done two things which take me onto my second point. I have in the past taken a few weeks out of the specification to look at current/controversial/interesting topics, in a fairly structured and ordered way, attempting to paint a broad picture of contemporary economic issues. It actually (controversy klaxon) involved a few videos as stimulus – Inside Job; TED talks and the like – but with commentary, follow-up and importantly, a planned progression of ideas. I also tend to devote a few lessons to some explicit Economic History and History of Economic Thought.

None of this is explicitly examined, but I want the second year course (thinking especially of macro, but maybe also monopoly power, labour markets, role of the state) to be built on foundations not just of what is in the specification, but the true, historical foundations these topics rest on. Whether I succeed or not, I am never really sure, and I too am guilty of superficiality here by virtue of the short time I have to play with. But I deliberately try to build a historical and political hinterland to the ideas we are yet to cover.

This is because one area of thought or technique of which I have become increasingly fond is the notion of narratives; my second point. Over the years, the more I have wanted to discuss a topical issue, the more concerned I have become with explaining its background, and to me, that means narratives and history.

David Didau tweeted the other day, riffing off Oakeshott, that “The more progressive your ends, the more traditional your means should be”. I think there’s a parallel here: I find being topical is likely to need more and more background and explicit teaching, and with the pace of economic change and the extraordinary times we are living in, that’s only going to continue.

You could make a (forced and imperfect) analogy with the Uncertainty Principle: I would love to see a slight shift of focus to broad narrative, context and history, in order to understand current and topical issues. But within the confines of an A Level, that means an opportunity cost: try to fix your position in current, topical issues and you don’t have the ability to cover where we’ve come from and where we’re going.

Devote more time to the broad sweep of history and you perhaps have less opportunity to analyse the real world as it is today, but I think (hope?) that students might better understand the topical issues you do cover.

But that runs into a massive roadblock, as must this post, so excessive and rambling has it become. It is that of assessment. I like to think I have alighted on a reasonable way to teach the whole course, with topicality and history in reasonable proportion, the latter informing the former. But that only really works if the examination is a bit more accommodating towards analogy, allusion, and broad, interesting essays, rather than nitpicky tickboxy mark schemes. It gets us into Reliability and Validity of Assessment; into choosing the narratives we teach; into explicit and tacit knowledge, and a whole host of other issues. They will have to wait, and this will be the end of a rather inconclusive post which raises more questions than it answers.

*****

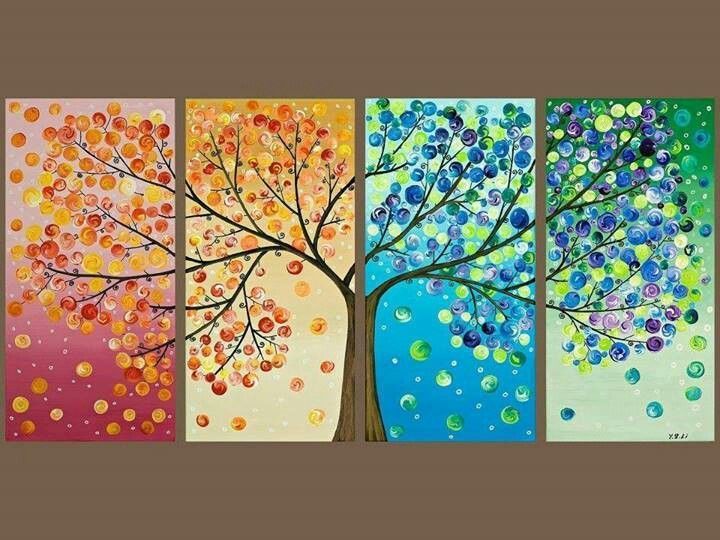

That was to have been the end, but then Martin raised a lot of the same ideas in this (let’s face it, more elegant) post. He is a great fan of metaphors, and with his Russian Dolls, he also mentioned the classic phrase of “not seeing the wood for the trees”. That got me think about whether what I’m grappling with here is “not seeing the tree for the leaves”.

A heavily topical approach is perhaps one of focus on the leaves, the superficial, the surface. And when you step back, what do you have? Perhaps a fuzzy tree, but perhaps just a pile of leaves. Perhaps in autumn: some red, some gold, beautiful, delicate… crumbling.

Painting by Jesse Dunlap, found here:

https://www.saatchiart.com/art/Painting-A-Pile-of-Leaves/161066/1162574/view

Have you really grasped the tree-ness of the thing? Where did those leaves come from? They grow out of branches, jutting forth from trunks, held down by roots. It has the surface feel of a tree, but to explain what a tree is we need the structure, the story of its growth, the understanding that it is sometimes in blossom, sometimes bedecked with leaves, sometimes bare.

Painting found here: https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/205828645445141070/

Bruegel knows what a tree is:

* This, of course, is part of the problem, that Economics has failed to integrate these issues into its core ideas, which gives rise to calls for more pluralist approaches. A typical example is…

**…Behavioural Economics, where it remains unclear how there can be integration. If it weren’t just an add on, what would that make Economics as a subject? Should economics be narrower and leave behaviour as a separate subject? If there are few laws of human behaviour, does economics have to give up its project of micro foundations? Is Behavioural Economics even unified and clear, and… true?

One thought on “Stationary Time Series/On Topicality, Part 2”